The afternoon before the trek I checked in at the Gibbon Experience’s office in Huay Xai and received instructions to pack light – just water, one change of clothes, sunscreen, a camera, long socks (to keep off the leeches), a toothbrush, hiking shoes, and a backpack. That’s it. I asked what kind of shoes they recommended and a soft-spoken French guy working behind the desk directed me to a nearby store that sold Chinese-made plastic shoes for $2. They looked more like slippers than hiking boots, but I took his advice and bought a pair.

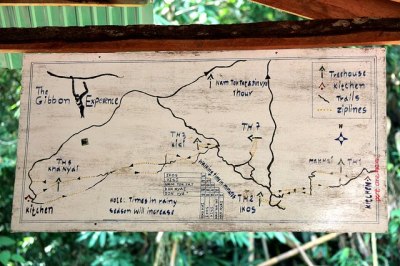

After a half hour of waiting on the front porch of a store we got antsy and wanted to know our next move. Our guides had disappeared so we talked to the minivan driver, who told us we would be hiking for two or three hours. When I first signed up for the Gibbon Experience they said bad weather sometimes extends the amount of trekking required to reach the treehouses and that everyone should be prepared to hike up to seven hours on the first day. If we only had to hike two or three hours, that meant we were avoiding the worst-case scenario.

The guides reappeared and off we went. Almost immediately the trail turned muddy and crossed several streams, making it clear why the plastic Chinese shoes were perfect – the water and mud wiped right off, and the soles had cleats that provided great traction. Normal hiking shoes didn’t fare nearly as well – they became caked in mud and were impossible to keep dry.

Slogging through the muck, up and down hills, in tropical heat and humidity quickly took a toll. We were all panting and covered in sweat. For a while I walked next to Vong, the Lao guide, and she mentioned that the Gibbon Experience’s truck was broken, which is why we had to hike that section of the trail. The Australian girl and her mother started to struggle and Vong dropped back to stay with them.

About two hours into the hike we stopped for lunch. The French guy gave us sandwiches and showed us a path from the trail to a plastic tube that had water flowing from it, apparently safe to drink. “How much further are we hiking?” I asked, assuming it couldn’t be more than an hour.

“Maybe 2-3 more hours until the village,” said the French guy. “Then another hour or so until the zip-lines.” Ooof… You’d think I would have learned my lesson about making assumptions in Laos. On we went.

It didn’t take much longer before references to the Bataan Death March began to pop up. The British couple had fallen way behind the main group, but we saw a motorbike go by with the Australian mother on the back – the guides had helped her hire a villager to drive her up the trail.

At some point Kane mentioned that the quiet French guy was actually the founder of the Gibbon Experience. Really? The big boss was the guy who carried our sandwiches and hardly said a word? Not long afterwards the French guy asked me about my camera and I took advantage of the opening to interrogate him, starting with the obvious first question. “My name is Jeff,” he said. A French guy named Jeff – off to an interesting start already.

Jeff first came to Laos in the mid-90s on a two-year contact to teach statistics at the university in Vientiane. An avid climber, he started using his free time to explore remote forests in search of tall trees. Once he learned to speak Lao his strategy was to befriend a government official in the area he wanted to explore and then accompany that official to the local villages. He did this to show the villagers he was on good terms with the authorities; otherwise they would have been suspicious of a strange Falang wandering around their jungle climbing trees.

On his climbing trips Jeff saw terrible things happening to the pristine forest – logging, slash-and-burn agriculture, the poaching of endangered animals – and he began to wonder what might be done to reduce the damage. He asked local farmers and hunters for their ideas. He spoke with government officials, worked out conservation plans, and applied for grants. But after several years of hitting one obstacle after another he didn’t feel good about his progress and decided to return to France.

In France Jeff landed a job in the Mergers and Acquisitions group of a big management consulting firm. (“They thought if I could negotiate agreements with Lao hill tribes I could handle the problems associated with merging corporate cultures,” he said.) But he wasn’t happy. His mind kept wandering back to the jungle. He realized he was speaking Lao in his dreams. After a few years in France he decided he had to go back to Laos and try again.

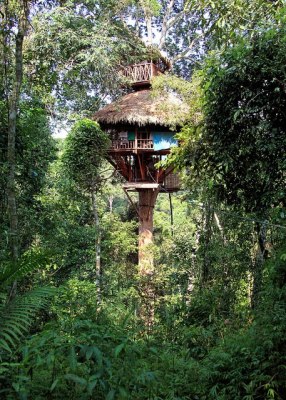

This time the barriers began to fall. Jeff found that the relationships he’d built with government officials and the locals were still strong, and international interest in conservation was higher than it had been just a few years before, making grants easier to secure. Jeff knew he wanted to bring tourists into the jungle canopy but he wasn’t sure what form the experience should take. Then one day it crystallized for him: zip-lines connecting a network of treehouses, with a focus on observing Black Gibbons in the wild.

The Gibbon Experience would be the revenue generator for a much larger conservation project that involved the entire community in and around the Bokeo Nature Reserve. Poachers would be talked into becoming tour guides or park rangers, protecting animals instead of shooting them. Slash-and-burn farmers would be shown how to cultivate and harvest rice paddies. Political pressure would be used to prevent loggers from violating protected areas.

Jeff’s vision was to create an integrated system that protected the environment while simultaneously providing an economic benefit to the community. He knew poachers would keep hunting unless they could make more money being guides or rangers. Farmers would revert to slash-and-burn if rice paddies didn’t turn out to be an easier way to feed their families. But he couldn’t fund all of that unless he had money coming in, and he couldn’t have money coming in until he had an experience to sell to tourists. Jeff had to convince the hunters to become guides and rangers before he had a way to pay their salaries. “So how did you do that?” I asked.

“A lot of drinking,” he said with a laugh. Shot after shot of Lao whiskey, critical for building trust. “In those days, hangovers were the toughest part of my job.”

Gradually he converted the hunters and about five years ago the first treehouse went up. Jeff introduced tourism slowly, limiting the number of visitors and – until just recently – positioning the project as an experiment. He admits there have been a lot of bumps in the road, but today there are almost 100 people working directly for the project. All of the salaries are paid by the money generated through the Gibbon Experience, including the salaries of the park rangers who protect the Bokeo National Reserve from rouge poachers. The success of the project has increased Jeff’s influence with government officials, which in turn makes it easier for him to put pressure on loggers who target protected lands. Many locals who used to practice slash-and-burn are now farming rice paddies given to them by Jeff’s project. (“If we can get a family to farm a rice paddy for two or three years, they never want to go back to slash-and burn,” Jeff said. “Slash-and-burn is more work.”) Unlike slash-and-burn, rice paddies are sustainable and don’t require large amounts of land.

Jeff is considering a range of options for applying his vision to other areas in Laos. He said he recently found what may be the biggest tree in the country and he’s thinking about building another experience around it. “What was it like to climb the biggest tree?” I asked.

“I didn’t climb it,” he said. “Only for worship.” Whoa… Deep! I decided Jeff probably wouldn’t have been interested in the Karaoke Booze Cruise on Halong Bay.

What this guy has accomplished is truly incredible. And here he was, hiking with us through the mud, apparently only telling his story because it would seem rude not to answer direct questions.

Finally our main group arrived in the small village of Baan Toup, right on the edge of the Reserve. I didn’t waste any time finding the village’s store – a Coke, even a warm one, brought me back to life.

Soon the local guides brought over our zip-lining harnesses. Jeff showed us how to get into the harness and we suited up, loving the idea of flying through the air instead of trudging through the mud. I thought the first zip-line would be nearby, but of course we had to hike a while to reach it.

My first experience soaring out over the jungle canopy was a legitimate rush. The metallic whirr of the pulley wheels on the cable, the feel of the harness straps suddenly supporting my weight, speed building up so quickly that within seconds I was effortlessly flying over the jungle canopy, hundreds of feet in the air. The contrast to the grueling slog earlier in the day couldn’t have been more extreme. Amazingly fun.

On my first zip-line I concentrated on enjoying myself and not screwing up. On my second zip-line I strapped my camera around my neck and took a video.

The treehouse was incredible. It had three levels: a main floor with a kitchen (including a refrigerator powered by a solar panel), an attic with a hammock and room for one bed, and a lower floor with a bathroom that had a rainwater shower. From the shower you could look out across the jungle canopy, separated by nothing but a thin railing; below your feet, through the spaces in the wooden beams, you could see water drip onto the leafy green tops of shorter trees. Most of us were too exhausted to shower that night, but we took full advantage the next morning.

Soon we heard the whirr of the zip-line and saw one of our guides flying towards us with a big pot of boiling water. As he prepared coffee and tea, another guide zipped in with dinner – steamed rice, pork, and vegetables, all very good, especially considering the fact that we happened to be in a tree.

A cold Beer Lao would have been perfect, but Jeff explained why he prohibited alcohol in the treehouses – in addition to the obvious danger of someone getting drunk and falling 200 feet to the ground, he worried that it would encourage the nearby villagers to hang around the treehouses trying to sell drinks, which he thought would diminish the experience. He delivered a line that sounded well-used: “You’re high enough already.”

After dinner we asked Jeff how often he hikes into the jungle with tourist groups. “Usually just once a month, but recently more often because of the fire.” Two weeks earlier, he told us, a group of Brits failed to blow out a candle when they went to sleep and the resulting fire completely burned down Treehouse #1. Jeff seemed philosophical about the setback. “We learned a lot, and nobody was hurt.” The accident spurred some changes: no more easy-burning thatch roofs, and no more candles in the treehouses (a rule Jeff mentioned, apparently without irony, as he lit a cigarette). Jeff and his team were working to rebuild Treehouse #1, otherwise he probably wouldn’t have joined our hike.

The guides set up three sleeping areas for us – two on the main level and one in the attic. The Australians and the German girls took the two areas on the main floor and I made my way up to the attic, dodging softball-sized spiders as I climbed the stairs. After one day in the jungle I was dehydrated, hot, caffeine-deprived, dirty, sweaty, exhausted, and happy.

Rob,

Not only you're a talented photographer, you also write very good adventure blog. I enjoy outdoor and photography and your works give me more inspiration to try harder at my age:-). Thanks for the greatest blog I've ever read.

I was in Sapa two years ago and probably took pictures of the same girls you took. Next year I'll visit Hue and Laos. Your adventures makes me anxious for the opportunity. Thanks again.

Don

LikeLike

Rob,

Great stuff as usual. I'm thoroughly enjoying your blog–I find myself sad when I check it on a day when you haven't posted anything. You've almost achieved “I can't imagine a world without” status 😉

Safe travels,

Stosh

LikeLike

Thanks Don and Stosh – glad to know someone is actually reading this!

LikeLike

Glad you saw so many gibbons on this experience. (P/s: You're crazy.)

LikeLike

You want gibbons? Check out Part 2…

LikeLike

Best post yet. Nice video of the zip line.

LikeLike